by ptfadmin | Jul 31, 2025 | Health Tips

Reviewed by Tyler Tice, PT, DPT, OCS, ATC

Cupping therapy is a traditional healing method that has been used by practitioners around the world for centuries. Across the world the method used to perform cupping and the theory behind the practice is quite varied however the basics are relatively the same, a vacuum is created using a small cup to pull the skin up into the cup. This suction is believed to bring blood with nutrients to the area or in eastern medicine they believe that it brings “bad blood” to the surface.

There are different methods used for cupping including dry cupping, wet cupping, fire cupping, and dynamic cupping. The two that are used by physical therapists are the dry and dynamic cupping methods. There is little understanding of what it is actually doing to the body but has been shown to greatly help patients with pain management and improve range of motion. There are many theories to explain the effects of cupping, some believe that the suction and pressure stimulate nerve fibers that interrupt pain signals to the brain. Others believe that the discomfort distracts the brain from the pain. Many also believe that cupping boosts circulation and nutrient delivery to the area allowing for the body to heal more efficiently.

What is the difference between dry cupping and dynamic cupping? Dry cupping is the most common method used, where multiple suction cups are placed over the muscle belly and left in one place for 5-10 minutes. Dynamic cupping is where the therapist or practitioner uses the suction cup to go back and forth across the muscle belly to bring the suction effects to the entire area and then many times are left in one spot to gain the same effects of dry cupping. While there is not a lot of research to explain why to use one method or the other, there is a main school of thought. Dry cupping is used for small muscles and deep muscles to improve blood flow and primarily for specific targeted pain modulation. This makes this option great for patients who have chronic pain or an old deeper injury.

Dynamic cupping is beneficial to be used over larger muscle areas such as the back, shoulders, or thighs. The movement of the cup is to help loosen tight muscles and fascia more evenly. The benefit of dynamic over traditional cupping is that it is believed to help increase range of motion by increasing flexibility and mobility of the soft tissues. This makes it more desirable for athletes and those who are struggling with muscle stiffness. It is also less intense and more tolerable by patients as it feels more like a deep tissue massage, leads to less bruising, and breaks up adhesions to relieve knots in the muscles.

When done properly, cupping is a very safe modality to be used in a physical therapy session for pain modulation and range of motion. It is expected for the patient to experience mild redness, bruising, soreness, and fatigue following the use of cupping. Patients are not candidates for cupping if they have active infections, skin wounds, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), blood disorder, cancer, organ failure, are pregnant, or are on blood thinners. Cups should be cleaned after use and between patients, practitioners should wear PPE, and the treatment area should be disinfected to prevent the spread of diseases.

- Furhad S. Cupping therapy. StatPearls [Internet]. October 30, 2023. Accessed June 15, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538253/.

by ptfadmin | Jul 25, 2025 | Health Tips

A concise synthesis of the NSCA Tactical Annual Training session (Season 6)

Reviewed by John Baur, PT, DPT, OCS, CSCS, FAAOMPT

What is “micro‑dosed” training?

The presenters define micro‑dosed programming as distributing the same weekly or micro‑cycle workload across multiple, very short sessions—often ≤ 15 minutes—rather than packing it into a few long workouts. Typical duty days for military, fire, and law‑enforcement personnel are fragmented; sliding in several bite‑sized bouts (e.g., a five‑exercise strength cluster at morning muster, a 10‑minute HIIT block before lunch, and a mobility finisher at shift‑change) keeps cumulative volume high without overwhelming the training calendar.

Tactical advantages at a glance

| Constraint in tactical settings |

Micro‑dosed solution |

| Unpredictable schedules (call‑outs, late dispatches) |

Sessions so short they can be paused or rescheduled without derailing the plan. |

| Limited equipment/space |

Focus on multi‑joint movements, sandbags, kettlebells, and body‑weight drills that need minimal set‑up. |

| High fatigue from job tasks |

Sub‑maximal loads and low per‑bout volume help manage overall stress while still driving adaptations. |

| Need for year‑round readiness |

Frequent exposure to all physical qualities (strength, power, aerobic capacity) maintains “training fingerprints” even during high‑tempo operations. |

Key programming principles

- Volume is sacrosanct – keep weekly tonnage or total sprint distance identical to a traditional plan; only the density changes.

- Frequency ↑, session length ↓ – most models use 5–10 micro‑sessions per week.

- Multi‑joint > single‑joint – compound lifts yield the greatest stimulus‑to‑time ratio (e.g., trap‑bar deadlift, push‑ups, kettlebell swings).

- Brief dynamic warm‑ups – substitute lengthy mobility routines with 1–2 sub‑maximal sets or movement‑specific drills to preserve minutes.

- Intensity stays on target – load (% 1RM), velocity, or target heart‑rate zone remains aligned with the training goal; only rest intervals and bout duration shrink.

- Strategic recovery – pepper easy mobility or breathing sessions between high‑output days to modulate fatigue.

Evidence snapshot

| Study cited in the presentation |

Finding |

Take‑home for TSAC |

| Kilen et al., 2015 |

Split daily strength work into short a.m./p.m. bouts—strength & hypertrophy matched traditional single sessions when total volume was equated. |

Micro‑dosing preserves gains if volume‑load is matched. |

| Astorino et al., 2012 |

Very‑short HIIT blocks delivered a significant ↑ in VO₂ max compared with moderate steady‑state. |

Small‑volume HIIT is a high‑ROI conditioning tool. |

| Prestes et al., 2017 |

Rest‑pause sets (a micro‑dose inside one exercise) improved muscular endurance and quad size in trained lifters. |

In‑set micro‑dosing (rest‑pause) is a time‑efficient hypertrophy tactic. |

(All three studies are referenced in the official NSCA quiz hand‑out)

Implementation template for a 5‑day duty roster

| Day |

Micro‑dose #1 (≤ 8 min) |

Micro‑dose #2 (≤ 12 min) |

| Mon |

Dynamic warm‑up + 2×6 trap‑bar deadlift @ 80 % 1RM |

HIIT: 6×15 s hill sprints / 45 s walk |

| Tue |

Push‑up ladder to 60 total reps |

Mobility flow (hip/shoulder) |

| Wed |

KB Swing 10×10 EMOM |

Farmer‑carry relay 6×40 m |

| Thu |

Box Jump 5×3 @ < 0.45 s ground contact |

Med‑ball rotational throw 5×5/side |

| Fri |

Goblet squat 4×12 @ RPE 7 |

Rest‑pause pull‑ups to 30 total reps |

Common pitfalls & solutions

| Pitfall |

Quick fix |

| Cutting intensity instead of density |

Keep loads/velocities honest; trim set length, not effort. |

| Skipping warm‑up entirely |

Use the first sub‑maximal set as the warm‑up. |

| Overlooking recovery |

Track HRV / RPE across the week; micro‑dosed does not equal over‑dosed. |

Test your grasp

| # |

Questions |

Answers |

| 1 |

What is the main characteristic of a micro‑dosed program? |

B. Total volume within a micro‑cycle divided across frequent, short‑duration, repeated bouts |

| 2 |

What is a key distinction between time‑saving and time‑efficient training? |

B. Time‑saving training focuses on reducing total time, regardless of frequency |

| 3 |

Which training variable is emphasized most in micro‑dosed programming? |

B. Training frequency and volume |

| 4 |

Which term best describes a “two‑a‑day” training method? |

B. Double‑split training |

| 5 |

Which warm‑up method is appropriate for micro‑dosed resistance training? |

C. Use of sub‑maximal weights or brief dynamic warm‑ups |

| 6 |

What type of exercises are prioritized in micro‑dosed resistance training? |

B. Multi‑joint movements |

| 7 |

Which training method offers a large return on investment for body composition and lower‑body power? |

A. High‑Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) |

| 8 |

What did the Kilen et al. (2015) study show about micro‑training? |

B. It showed similar adaptations to longer sessions when volume‑load was equal |

| 9 |

What adaptation did the HIIT group experience in the Astorino et al. (2012) study? |

B. Increase in VO₂ max |

| 10 |

In the Prestes et al. (2017) study, rest‑pause training improved which outcome? |

A. Muscular endurance |

Bottom line for TSAC facilitators

Micro‑dosed programming lets you “thread the needle” between operational chaos and physiological progression. By keeping the volume constant, intensity appropriate, and sessions surgically brief, you can maintain—and often improve—strength, power, and conditioning without monopolizing precious duty hours. Pair the model with smart monitoring (RPE, wellness checks) and it becomes a sustainable, evidence‑backed strategy for tactical populations year‑round.

by ptfadmin | Jul 20, 2025 | Health Tips

A Brief Systematic Review and Meta analysis (Strength & Conditioning Journal, 2025)

Reviewed by John Baur, PT, DPT, OCS CSCS, FAAOMPT

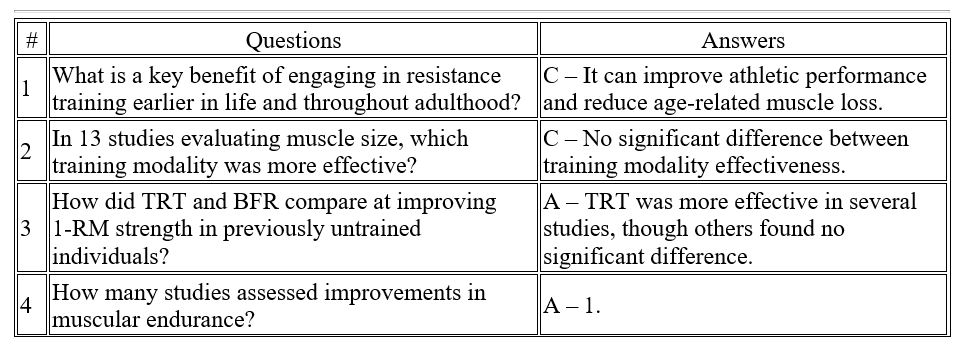

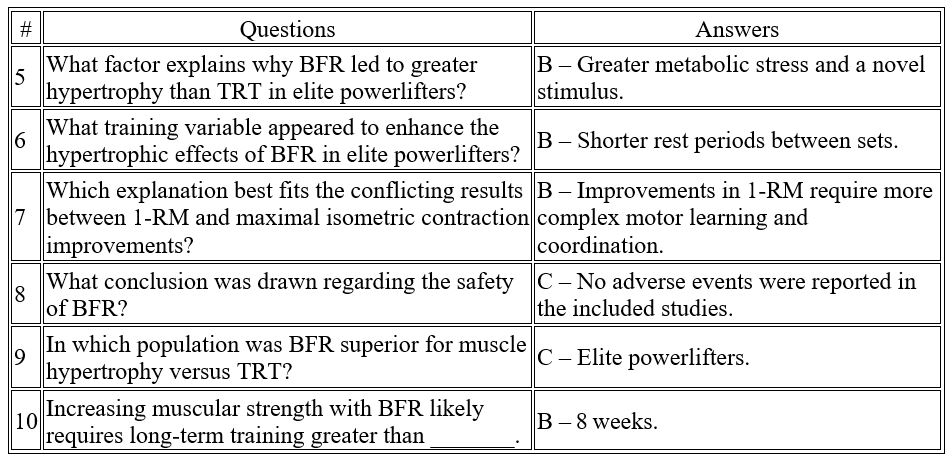

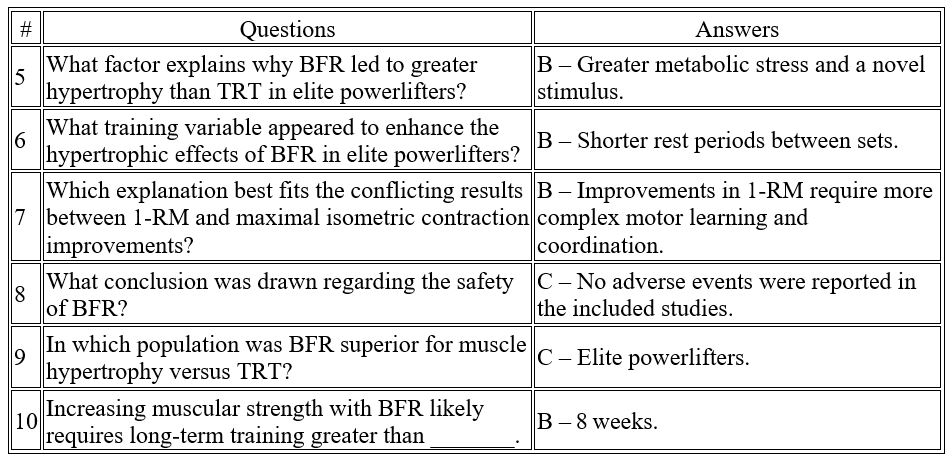

This systematic review and meta‑analysis set out to determine whether low‑load blood‑flow‑restriction (BFR) resistance training can match or outperform conventional traditional resistance training (TRT) for increasing muscle size, strength and endurance in healthy adults. Twenty randomized controlled trials (541 screened records, 20 included) met pre‑defined PICOS criteria; seven contributed hypertrophy data and nine contributed strength data to the quantitative analyses.

- Primary outcome – muscle hypertrophy: 17 of 20 trials reported significant growth with training. A pooled effect size of 0.045 (95 % CI –0.278 to 0.367) indicated no statistical difference between BFR and TRT for increases in whole‑muscle CSA or volume.

- Secondary outcome – strength: Nine studies entered the meta‑analysis (1 RM, isometric or isokinetic tests). The pooled effect size of –0.149 (95 % CI –0.439 to 0.141) likewise showed no significant difference in strength gains between modalities. Qualitative trends suggested TRT may yield faster early‑phase 1 RM gains (< 8 weeks), whereas BFR “catches up” with longer training (> 8 weeks).

- Muscle endurance: Only one study assessed endurance; both methods improved repetitions‑to‑failure equally, preventing firm conclusions.

- Contextual moderators: Rest intervals, training to failure, programme duration and athlete training status moderated results. For example, BFR out‑performed TRT for quadriceps hypertrophy in elite powerlifters—possibly due to the novel metabolic stress imposed by short‑rest, low‑load occlusion work.

- Safety profile: Across all trials no adverse events were reported, supporting BFR as a safe alternative when heavy loading is undesirable or contraindicated.

Practical takeaway: Coaches and clinicians can prescribe low‑load BFR to build muscle and strength when heavy loading is impractical, ensuring programmes run ≥ 8 weeks and use appropriately short rest intervals to maximise metabolic stress.

by ptfadmin | Jul 17, 2025 | Health Tips

Reviewed by Madison Hof, SPT

Introduction

Though conventional Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) procedures have yielding good long-term results in the past, robotic-assisted TKA was introduced to improve implantation alignments, particularly in younger patients. These alignment improvements were studied in this randomized controlled trial to determine if robotic-assisted TKA results demonstrate improved long-term outcome scores or implant survivorship. A large randomized, controlled trial was conducted using patients who received either robotic-assisted or conventional TKA procedures and have reached long-term (10-year minimum) follow-ups to determine if robotic-assisted TKA is superior. Terms for determination include (1) functional results based on Knee Society, WOMAC and UCLA Activity scores, (2) radiographic parameters, (3) Kaplan-Meier survivorship, and (4) complications specific to robotic-assistance, including pin tract infection, peroneal nerve palsy, pin-site fracture, or patellar complications.

Patients and Methods

1406 eligible patients were selected from one performing surgeon with surgery dates ranging from January 2002 to February 2008. 700 patients (750 knees) received robotic-assisted TKA and 706 patients (766 knees) received conventional TKA. 674 patients from the robotic-assisted TKA group and 674 patients from the conventional TKA group were available to be evaluated for clinical, radiographic, and CT scans at follow-up at an average of 13 (+/-5) years post-op. The robotic assisted TKA group consisted of 542 women and 132 men with an age range between 49 to 65 years old. The conventional TKA group consisted of 530 women and 144 men with an age range between 46 to 65 years old.

Patients from both groups were ambulatory using either crutches or a walker on the second postoperative day and were all discharged to home. Medical advice was given to all to use their assisted devices for 4 to 6 weeks and a cane thereafter as needed to prevent falls. Postoperative follow-up examinations were performed at 3 months, 1 year, and every 2 to 3 years thereafter.

Results

Functional Outcomes

It was found that there was no difference in clinical outcome measure at the most recent follow-up for those who received robotic-assisted TKAs compared to those who received conventional TKAs. Mean total Knee Society knee scores, residual pain levels, WOMAC scores, ROM, and mean UCLA activity scores showed no difference in outcomes.

Radiographic Outcomes

According to radiographic parameters measures, including limb alignment, component alignment, and aseptic loosening, there was no difference in outcomes found between groups. The rotational alignment of the femoral component from the transepicondylar axis or tibial component also showed no difference.

Component Survivorship

Both groups showed the same percentage of implant survivorship (98%) at 15 years after the operation.

Complications

The frequency of complications yielded no difference between groups. Four knees in each group acquired a superficial infection and were treated with intravenous antibiotics for 2 weeks. There were no reports of deep infection, pin site fracture, pin tract infection, patellar dislocation, patellar fracture, supracondylar fracture or peroneal nerve palsy in either group.

Discussion

It was found in this randomized controlled trial that there was no difference in outcome scores, mean implant or limb alignment, survivorship, or complications between individuals who received a robotic-assisted TKA versus individuals who received a conventional TKA at an average 10 year follow up. However, a small reduction in the proportion of knees aligned more than 3 degrees away from neutral using robotic-assisted methods was found. Meaning, there were less knees in robotic-assisted TKA that were misaligned from neutral more than 3 degrees. This demonstrates that the overall knee positioning in robotic-assisted TKA achieved more precise neutral mechanical axis alignment than conventional TKA.

Limitations of the study include having no morbidly obese patients evaluated, which is a group who may benefit more from robotic assisted procedures given the difficulties associated with identifying landmarks with a conventional TKA procedure. This study also included a population of predominantly women with low body weight and good preoperative ROM which these factors could limit the applicability of this study to other patients.

Reference

Kin YH, Yoon SH, Park JW. Does Robotic-assisted TKA Result in Better Outcome Scores or Long-Term Survivorship Than Conventional TKA? A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2020;478(2):266-275. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/corr.0000000000000916

by ptfadmin | Jul 10, 2025 | Health Tips

Reviewed by Madison Hof, SPT

Introduction

Treatment for tendinopathies should be viewed as a multimodal approach, targeting not only the peripheral tissue but the neuromuscular adaptations that occur with persistent pain as well. Addressing the corticospinal control of the muscle by motor activation as a result of excitatory and inhibitory inputs ultimately affects tendon loading and motor production. It is important to consider neuromuscular control of the asymptomatic side as well, comparing side-to-side differences as well as differences in motor control in people with and without tendinopathy.

Motor control in people with and without tendinopathy

Muscle strength is often studied in tendinopathy research as compared to motor control. It has been understood that there is no consistent pattern of strength or performance change (increase or decrease) in tendons being studied such as in Achilles, patellar and RTC tendinopathies as well as in diagnosis such as lateral epicondylalgia. Strength deficits coupled with the presence of tendinopathy has not been consistently demonstrated in past research to reasonably target the peripheral tissue’s power production alone without assessing the neuromuscular component of muscle activation.

Imbalances in recruitment ability of excitatory and inhibitory influences around the painful tendon during muscle loading were found when comparing symptomatic and asymptomatic sides of athletes with patella tendinopathy (PT). It has been hypothesized that a protective adaptation occurs, reducing the mechanical demand that is placed on the tendon. Both peripheral and central contributions are associated with motor control changes and those with PT demonstrated landing mechanic patterns with less variability than to those without PT. Motor patterns that are invariable implies that control coming from the corticospinal tract is altered and may be due to protective strategies. Jumping abilities with less variability has been shown to be a risk factor for developing PT. In fact, these individuals were shown to be better jumpers than those without PT, coining this phenomenon the ‘jumper’s knee paradox’. Therefore, movement variability has been hypothesized as an important attribute in preventing injury.

Pain is commonly accompanied with changes in motor control as an adaptive mechanism that protects us from bodily threat. Motor control while having painful symptoms is altered due to the corticospinal drive to the motor neuron or muscle. Furthermore, there were no differences in muscle strength or activation between groups suggesting that the motor task can cause a potential pain response during jumping even in the absence of nocioception.

Motor control changes may be bilateral

Side-to-side strength deficits were found to be low following unilateral Achilles tendinopathy surgery which may reflect bilateral motor control deficits. These changes following tendinopathy pain may also be system wide which can be due to intrinsic and extrinsic factors, potentially increasing the risk of tendinopathy elsewhere in the body. An increase in global sympathetic drive implies the nervous systems’ involvement in tendinopathies. For example, there is increased inhibition responses on an affected limb following a stroke and an increased corticospinal excitatory response on the unaffected limb. This indicates an increased interhemispheric inhibition from the non-affected hemisphere to the lesioned hemisphere leading to further inhibition on the affected limb during activation of the unaffected limb. Changes in the unaffected side associated with tendinopathies may be the bodies way to attempt motor control homeostasis while trying to protect a region. This may also explain the high injury prevalence of the contralateral tendon following rehabilitation.

Conclusion and clinical implications

In order to address the differences in excitability and inhibition, an alteration to corticospinal control of muscles must be acknowledged as seen in different motor strategies used for protection. Movement variability should be considered following musculoskeletal pain even if nocioceptive input is absent due to the fact that altered motor control could be transmitted to a tendon causing a continuation of previous nocioceptive input. Altered invariable movement patterns that occur with pain are presumed to optimize performance subconsciously. This is demonstrated in those with tendinopathy displaying superior strength and performance despite having inflamed peripheral tissues. Strength training is often the focus for individuals with tendinopathy to stimulate the physiological adaptation of the muscle/tendon, but it is now known that it can modulate pain and corticospinal control of the muscle as well. Rehabilitation should be considered bilaterally to address the unaffected side as well to prevent contralateral motor adaptations from developing.

References

Rio E, Kidgell D, Moseley GL, et al. Tendon neuroplastic training: changing the way we think about tendon rehabilitation: a narrative review. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2015;50(4):209-215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095215