Effectiveness of Unilateral Training of the Uninjured Limb on Muscle Strength and Knee Function of Patients With Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Education

Reviewed by Tyler Tice, PT, DPT, OCS, ATC

After ACL reconstruction surgery, the quadriceps muscle is commonly about 20% weaker on the surgical side than the healthy side. Recent evidence states that changes in the central nervous system can account for some of these deficits, which is why ACL rehabilitation plans need to also include strategies that address these central neural mechanisms and in turn reduce strength loss. Cross education is one such way to do this. Cross Education (CE) is the strength gain found when a patient performs a strengthening exercise program on the uninjured limb to maintain or even gain strength in the injured limb. This can be an effective strategy when a patient’s injury requires complete immobilization or has limited motion due to the recency of the injury. CE can induce structural and functional changes in the patient’s nervous system which increases their ability to activate the quadriceps muscle and thus increase its strength.

Methods:

This systematic review included 7 randomized control trials that met these specific criteria:

- Patients > 18 years old after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction

- Interventions used included unilateral strength, motor control, and balance training to the uninjured limb

- Plans utilized standard protocols of rehabilitation for ACL

- Strength testing was performed on quadriceps and hamstring muscles

- Study was a randomized control trial or controlled clinical trial.

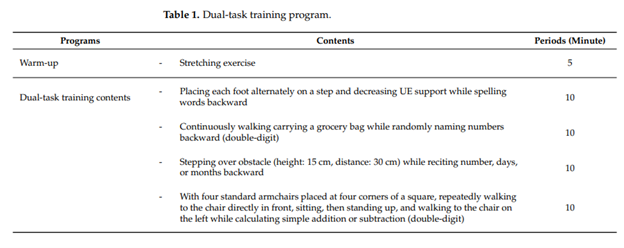

Individuals with other ligamentous injuries of the knee were excluded from this study. Each utilized a variety of training frequencies (2,3, or 5 times per week) and for varying total weeks of training time with 8, 24, 26 weeks total being most common. Several different measures were used among each of the studies to determine the effects of the CE through unilateral training including maximal voluntary isometric contractions (MVICs) of the quadriceps, self-reported knee function, and limb symmetry index (LSI) which is a ratio of the estimated performance of the involved limb and uninvolved limb.

Conclusions of the Study:

All the studies demonstrated a significant difference in quadriceps MVIC between participants who performed standard rehabilitation and unilateral training versus standard rehabilitation alone. The self-reported knee function measures were mostly inconclusive among all the studies, but one that determined at 8 weeks of rehabilitation there was a significant difference in knee function according to the participants suggesting a potential short term benefit to the CE. The LSI scores in studies that extended to the 24 and 26 week time frames demonstrated significant difference between groups who performed the unilateral training and standard rehabilitation and those who did not perform unilateral training. However, this measure is simply and estimation and can be significantly overestimate the functional abilities of an ACL patient at 6 months post-operation. The results of the study concluded that by including unilateral training in the participant’s rehabilitation program, the loss of strength typically experienced by the patients after an ACL reconstruction was reduced by 8.52%. This same effect has been even higher in other types of patients like those with osteoarthritis, multiple sclerosis, or other limb immobilizations and therefore would be an excellent addition for most ACL reconstruction patients.

Clinical Implications:

Through stimulating the nervous system and activating the spinal nerve pathways that contribute to movement of the uninvolved limb, ACL reconstruction patients could experience a protective effect to atrophy and strength loss of the quadricep muscle on the affected side by performing unilateral training of the uninvolved limb. PTs should include this in all stages of rehabilitation, but especially in the early stages when the patient is immobilized or has restricted motion due to surgical protocols. Exercises like the single leg squats or long arc quads that require high degrees of quadriceps activation could be great options to promote this protective effect, as long as it fits within the parameters of the patient’s surgical protocol.

References:

Cuyul-Vásquez, I., Álvarez, E., Riquelme, A., Zimmermann, R., & Araya-Quintanilla, F. (2022). Effectiveness of unilateral training of the uninjured limb on muscle strength and knee function of patients with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-education. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 31(5), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.2021-0204