My Shoulder is Frozen-What?

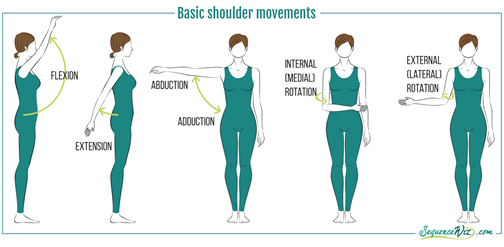

Adhesive capsulitis, more commonly known as frozen shoulder, is a debilitating and rapidly developing impairment of the shoulder. Adhesive capsulitis is defined as having a painful shoulder with pain present vaguely throughout the whole shoulder, with subsequent and rapidly progressing stiffness limiting range of motion in all directions (1). The typical loss of motion presents in the following manner, external rotation is most limited then abduction, and followed by shoulder internal rotation (2). The following images defines external rotation, abduction, and internal rotation:

Image courtesy of sequenewiz.com

Primary adhesive capsulitis affects 2%-5.3% of the general population (3,4). Secondary adhesive capsulitis affects 4.3%-38% of the population (3,4,5). Secondary adhesive capsulitis is that which derives from a known injury or an underlying systemic disease such as diabetes mellitus (type I or type II) or thyroid disease). A study by Milgrom et al discovered that of people with adhesive capsulitis, approximately 30% have diabetes, and around 21% of women had hypothyroidism (6). This is a disease and subsequent impairment which has a debilitating effect on a large portion of the population, and as seen above affects those with diabetes and thyroid disease at a higher rate than those without diabetes or thyroid disease. Adhesive capsulitis has also been found to be most common in people 40-65 years old, women>men, and those who have had adhesive capsulitis previously in the opposite shoulder, as well as those with Dupuytren’s disease (6,3,7).

Categories of Adhesive Capsulitis (1)

- Primary: Of unknown cause or origin

- Secondary: Of known cause or origin, especially injury or systemic disease

- Systemic: Diabetes or other metabolic conditions

- Extrinsic: Stroke, Heart Attack, Parkinson’s Disease, etc.

- Intrinsic: Rotator cuff tear, labral tear, biceps tendinopathy, etc.

Stages of Adhesive Capsulitis:

Adhesive capsulitis occurs in 4 progressive stages, which typically runs through a time period of approximately 18-24 months total. Adhesive capsulitis, unlike most other musculoskeletal conditions, dissolves of its own accord after this time frame and people typically return to pre-disease levels of pain and function, however residual stiffness and muscle tightness can be present. The stages of frozen shoulder are as follows (8,9,11):

- Onset (0-3 months from onset):

- Sharp pain at end ranges of motion

- Achy pain at rest

- Sleep disturbance

- Minimal to no ROM restrictions

- Freezing/Painful (3 months-9 months since onset)

- Gradual loss of overall shoulder motion due to pain

- Frozen (9 months-15 months since onset)

- Severe pain

- Extreme loss of shoulder motion all directions

- Thawing (15-24 months since onset)

- Pain begins to resolve

- Significant stiffness still persists

What Do I Do if My Shoulder Freezes?

The best recommendations based off the 2013 Clinical Practice Guideline for Adhesive Capsulitis recommends a combination of the following treatment interventions in order from strongest to weakest support from the evidence:

- (Strong Evidence): Corticosteroid injections from a qualified practitioner in combination with the shoulder stretching and strengthening.

- (Moderate Evidence): Patient Education on the course of adhesive capsulitis as well as activity modification to allow a minimal pain lifestyle, and physical therapy activities which match and do not aggravate the person’s current level of irritation and pain.

- (Moderate Evidence): Stretching exercises which match the intensity of your pain and irritability.

- (Weak Evidence): Modalities and passive interventions such as shortwave diathermy, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation.

- (Weak Evidence): Joint mobilizations or deep joint stretching to the affected shoulder with the goal of decreasing pain and improving range of motion.

- (Weak Evidence): Manipulation under anesthesia. This is a common practice but has in recent years been performed less frequently as most often the stiffness returns after the manipulation under anesthesia.

Physical Therapy First

Your physical therapists at Physical Therapy First will provide you with the highest quality of care for your full 60-minute session. Physical Therapy First is the only outpatient physical therapy clinic in the Greater Baltimore area providing 1-on-1 care with your physical therapists for your full treatment session. Call in any of our four locations in the greater Baltimore region today to be seen immediately for your shoulder pain!

References:

- Webpage: https://www.physio-pedia.com/Adhesive_Capsulitis

- Cyriax J. Textbook of Orthopedic Medicine. Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1970.

- Aydeniz A, Gursoy S, Guney E. Which musculoskeletal complications are most frequently seen in type 2 diabetes mellitus? J Int Med Res. 2008;36:505-511. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/147323000803600315

- Bridgman JF. Periarthritis of the shoulder and diabetes mellitus. Ann Rheum Dis. 1972;31:69-71.

- Lundberg BJ. The frozen shoulder. Clinical and radiographical observations. The effect of manipulation under general anesthesia. Structure and glycosaminoglycan content of the joint capsule. Local bone metabolism. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1969;119:1-59.

- Milgrom C, Novack V, Weil Y, Jaber S, Radeva-Petrova DR, Finestone A. Risk factors for idiopathic frozen shoulder. Isr Med Assoc J. 2008;10:361-364.

- Balci N, Balci MK, Tüzüner S. Shoulder adhesive capsulitis and shoulder range of motion in type II diabetes mellitus: association with diabetic complications. J Diabetes Complications. 1999;13:135-140. http://dx.doi. org/10.1016/S1056-8727(99)00037-9

- Hannafin JA, Chiaia TA. Adhesive capsulitis. A treatment approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000:95-109.

- Neviaser AS, Hannafin JA. Adhesive capsulitis: a review of current treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:2346-2356. http://dx.doi. org/10.1177/0363546509348048

- Neviaser RJ, Neviaser TJ. The frozen shoulder. Diagnosis and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987:59-64.