by John Baur, PT, DPT, OCS, FAAOMPT

The material for this article consists of a compilation of the evaluation and treatment techniques learned from Mariano Rocabado, PT, DPT while attending Basic Cranio-Facial (CF1), Intermediate Cranio-Facial (CF2) and Advanced Cranio-Facial (CF3) courses through the University of St Augustine and from peer reviewed journals. Dr. Rocabado is recognized internationally as an expert in the field of temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMD). This article contains an overview of diagnostic radiographic imaging and manual therapy treatment techniques for TMD patients.

A common focus in TMD treatment involves the position of the cranium and the mandible relative to the cranium. The term craniovertebral centric relation refers to the stability of Atlas and Axis and how Atlas is stabilized on Axis, and how the Axis is stabilized on C3.

In physical therapy the term craniovertebral centric relation refers to a three dimensional articular ligamentous position of the cranium over the upper cervical spine. The condyles of the occiput adopts a stable position over the first cervical vertebra (Atlas), which maintains a stable anteroposterior and lateral position with the odontoid process in a horizontal alignment over the shoulders of the Axis (C2). This relationship allows the occiput, Atlas and Axis to perform 50% of the function of the craniocervical unit. The Atlas, Axis (two atypical vertebrae) and C3 form the upper cervical spine and they perform 50% of the function of the neck.

The craniovertebral centric relation should not be confused with centric occlusion which is the relationship between the maxilla and mandible. The physical therapist treatment should focus on accomplishing a craniovertebral centric relation and congruency in the craniovertebral joints.

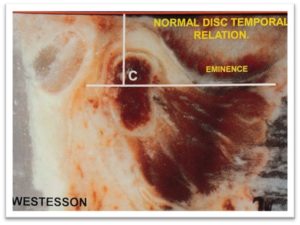

It is also important to understand the concept of the synovial joints of the TMJ and the idea that the temporal component of the joint has to be horizontal. The position of the temporal portion of the temporomandibular joint is related to the position of the cranium which is dependent on how the occiput relates to the craniovertebral joints. If the occiput is level horizontally in the sagittal plane and the patient has a functional craniovertebral angulation with adequate space between occiput and Atlas, than the TMJ disc is going to be related to the temporal bone in a horizontal position. Once the position of the disc is identified in the fossa, than the physical therapist should know where the condyle should be relative to the disc and the condyle and disc will be in the center of the fossa.

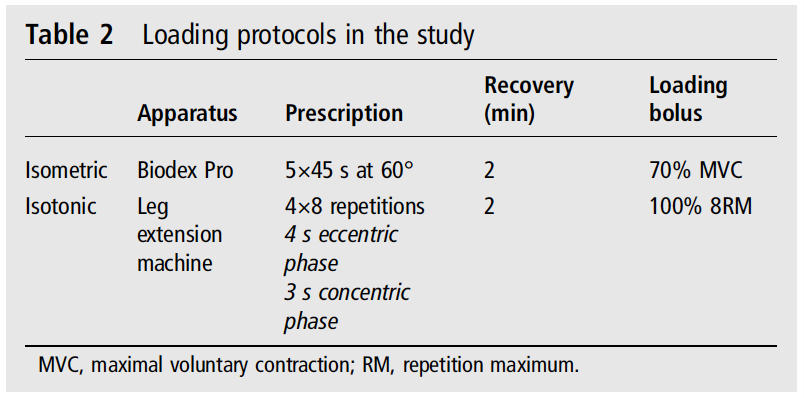

Normal Condyle-Disc-Temporal Relation (Westesson)

The condyle is related in the fossa once the temporal bone is horizontal, and once the temporomandibular disc is stable on the fossa. Once the occiput is in a horizontal position in the sagittal plane the horizontal position of the temporal bone must be determined. Next the physical therapist sketches a vertical line passing through the center of the fossa in the 12 o’clock position and a horizontal line in the 3 o’clock position. This disc should be anteriorly and in between the vertical and horizontal lines. Next to determine the position of a stable relationship between the condyle, the disc, and the fossa the physical therapist should understand the principle of centric relation.

Westesson angle – first determine the horizontal position of the temporal bone which is determined by the horizontal position of the occiput. Next trace a horizontal line tangent to the inferior border of the eminence. A perpendicular line can be drawn crossing the deep portion of the fossa. Both lines determine the position of the disc in the posterior wall of the eminence.

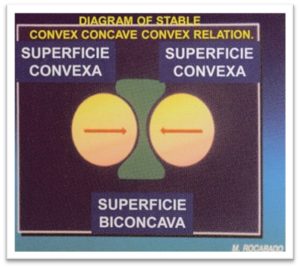

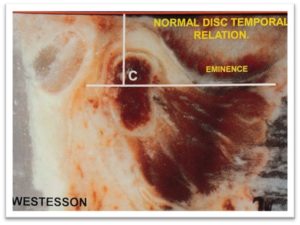

The active joint surface of the condyle it is convex and the active joint surface of the temporal component is convex. Thus, active joint surfaces of the active TMJ structures are both convex. When two convex surfaces gliding in opposite directions occurs in joint it produces “wear-and-tear” and degeneration. To change this relationship the disc provides a concave joint surface.

In the temporomandibular joint, there is a convex surface of the condyle that produces an inferior independent synovial joint. The convex surface of the temporal bone produces a superior independent synovial joint. This results in a convex on a concave inferior synovial joint and a concave on convex superior synovial joint.

The concave disc is needed for congruency and stability since the temporomandibular joint has two convex surfaces that face each other and it is inherently an unstable joint. Fifty percent of the TMJ function comes from the inferior synovium, and 50% function comes from the superior synovium. It is important that the two convex surfaces remain very tight together with the concave disc, where the convex and concave surfaces meet, in order for the joint to remain stable.

Craniovertebral Angle and Cervical Lordosis

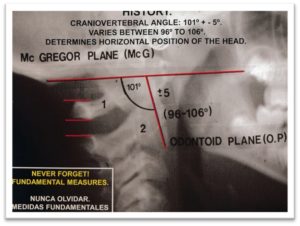

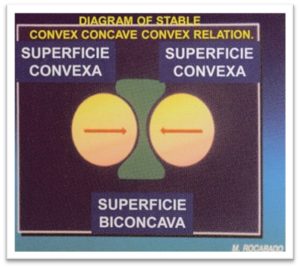

The second cervical vertebra (C2) is the most important vertebrae to exam at this level since it is the vertebrae that supports the weight of the cranium and distributes forces to the rest of the cervical spine. The position of C2 will determine the curvature of the lower cervical spine. A functional craniverbral angle should fall between 96 and 106 degrees and achieving this measurement should be one aim of physical therapy treatment. The physical therapist will want to accomplish centric relations and congruency in the craniovertebal joints and the dentist will want objective reasoning and measurements, and this can be accomplished by measuring the craniovertebral angle.

Cranioverbral Angle / McGregor’s Plane

The loss of cervical lordosis will increase the compressive forces and load through the cervical spine and can lead to cervical joint degeneration. So it is important to recognize the loss of cervical lordosis in developing children in order to prevent postural abnormalities that may cause degenerative joint changes and orofacial pain.

The craniovertebral angle, the angle between the cranium (basi occiput) and C2, plays a major role in establishing the cervical lordosis. It is also noting that the craniovertebral angle is important because of its impact on the sub-cranial space. Rocabado teaches the concept of the functional craniovertebral unit, the concept of the craniovertebral angle and the importance of adequate functional sub-cranial spaces. Also how the sub-cranial angle determines the curvature of the lower cervical spine.

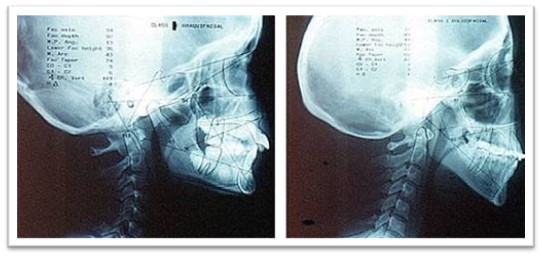

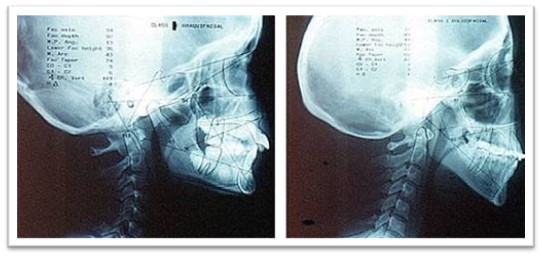

The below cephalometric radiographs demonstrate the association between the craniovertebral angle and lordosis in the mid/lower cervical spine. The radiograph on the right demonstrates sub-cranial backward bending, as seen by the narrowed space between occiput and the spinous process of C2. The cervical lordosis is consequently decreased or reversed.

The cephalometric radiographs on the left demonstrates normal position of the head and cervical spine and on the right a flattened cervical lordosis with sub-cranial backward bending.

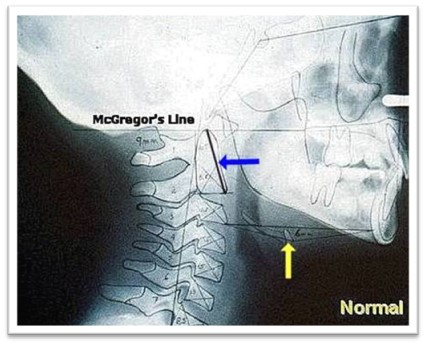

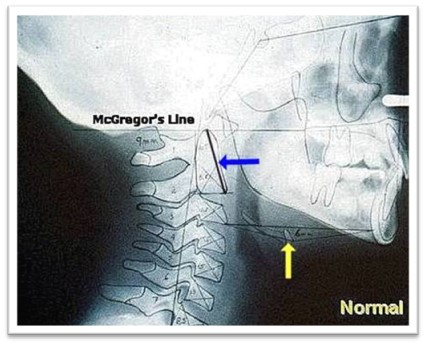

The sub-cranial angle can be assessed on a radiograph. The below image demonstrates the sub-cranial angle, formed by the McGregor’s line and the odontoid plane (blue arrow). The McGregor’s line is drawn from the posterior hard palate to the basi occiput and the odontoid plane from the anterior-inferior margin of the body of C2 to the tip of the odontoid. Where these two lines intersect there should be a 96-106 degree angle posteriorly (see radiograph below).

Cephalometric radiograph. Please note the position of the hyoid bone (yellow arrow) in line with the C3/4 interspace. Notice also the posterior arch of atlas in a mid-position between basi occiput and C2 spinous process, dividing the sub-cranial space in half.

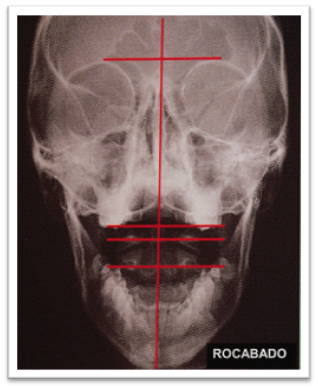

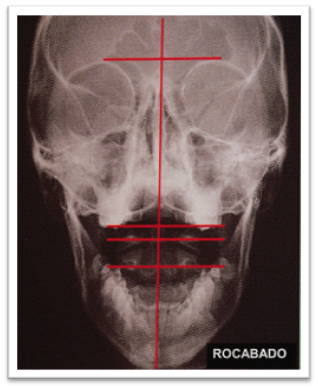

Skeletal Midline

Skeletal midline is an important component in establishing cranioverbral symmetry in the coronial plane. The Axis (C2) plays an important part in establishing skeletal midline because it is used as a reference point for creating the vertical vector through the dens and vertebral body. When C2 is in skeletal midline the spinous process should be vertically in line with the center of the dens. Dentist would determine skeletal midline when the patient swallows and bites the point at which the central line of the maxillary (upper) central incisor will coincide with the center of the mandibular (lower) central incisor. The center of the maxilla should coincide with the center of the mandible.

The skeletal midline of the craniomandibular joints is determined by a vertical line that crosses through the middle of the dens and the spinous process of C2. The second cervical vertebra acts as the base for the cranium and the Atlas is in between as a stabilizer. The cranium is also attached ligamentous with C2.

In this position, Atlas (C1) should be proportionally related on the left and right to the dens of the Axis. The inferior joint surfaces of Atlas will symmetrically on top of the shoulders of Axis in a horizontal position to allow Atlas to rotate. The Atlas is going to be sitting horizontally on top of Axis, perpendicularly. In order for the cranium to be horizontal in the coronal plane, C2 must be on a skeletal midline, with a craniovertebral angle between 96 and 106 degrees.

The midline of the maxilla and the mandible should be on a skeletal midline that corresponds to the skeletal midline of the craniovertebral joints. There should essentially be one skeletal midline that crosses the center of the cranium, through the center of the mandible and the middle of the cervical vertebrae. The dentist will try to get the mandible to the maxilla on a skeletal midline. Whereas the physical therapist has to coincide that skeletal midline with the midline of the craniovertebral joints in order achieve congruency and stability in centric relation.

If a patient can side bends to the right and not to the left than C2 is likely rotated to the right. The patient can side bend towards the problem, but not away. The spinous process will move in the opposite direction of the head. This is a good test for the stability of the craniovertebral joint mobility.

If the Atlas is not sitting on top of Axis in skeletal midline then the patient will not have normal function of the craniovertebral joints. If the patient does not have a cranium that is horizontally related in the sagittal plane or the coronal plane they cannot have a stable occlusion.

The occlusive contacts change depending on the position of the cranium. Different cranial positions will create different mechanics. The cervical joints need to have centric relations for normal patterns of growth and development.

Principles of Occlusion:

Everything is relative to how the mandible moves to the cranium. Physical therapists use to believe that all cranio-facial problems were caused by muscles. This belief was accepted for about 10 years. Then there was 10 years that were focused on occlusion or how teeth related to each other.

The front teeth help to guide the mandible forward until they are approximate. When the front teeth are edge-to-edge, the back molars should not touch and the mandible moves forward and down. The separation of the back teeth helps protect them. Canine guidance and incisive guidance are mutually protected system to decrease wear-and-tear of the teeth. The canines provide lateral guidance and the right canine protects the left and vice versa. The front teeth help provide anterior guidance.

The back molars are more powerful when biting than the front teeth and the canines are not as strong as back molars. A centric occlusion is when the joint surfaces are maximally congruent. When the TMJ cannot accomplish any further movement in a given direction it is in a close pack position.

In-occlusion means no contact between teeth and the TMJ is in a loose pack position. Occlusion means to close and this is when the TMJ is in a closed pack position.

The contraction of the muscles of mastication increases when the teeth are touching. The temporomandibular joints should not spend more than 15 minutes of a 24 hour period in a closed pack position and the teeth should not be in occlusion for more than 15 minutes a day. Thus, the teeth should be in a loose pack position for the majority of time. The amount of time that teeth are touching equals the amount of time that the muscles are contracting. The more time the TMJ is in closed pack position, the more time the TMJ is exposed to an isometric muscle contraction which can lead to para-function. It is important to keep your mandible at resting position in order to preserve or rebuild anterior guidance and to preserve or rebuild canine guidance for protection and muscle relaxation and to avoid premature degeneration.

The importance of sub-cranial spaces

A disturbance of the cranio-vertebral angle implies postural aberration and might indicate that physical therapy intervention is needed. Therefore it is important that we teach the orthodontists that we work with to measure the craniovertebral angle and palpation of the suboccipital triangle. The dentist will then have an objective way of knowing if the cranium is anteriorly or posteriorly rotated and if functional space is adequate, and can then decide whether to refer the patient to physical therapy. This assessment can be done easily.

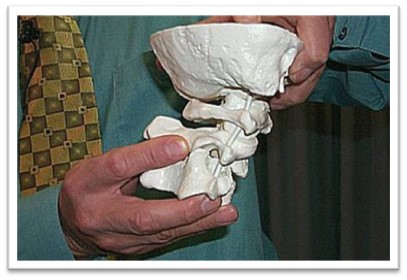

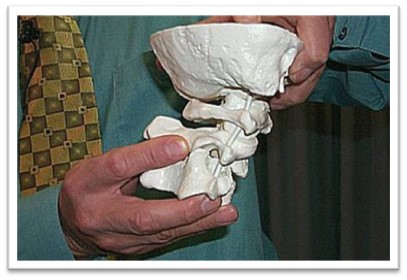

Atlanto-occipital backward bending demonstrated on a model

The space between the basi occiput and C2 should not be less than 20 mm and the physical therapist should be able to place a minimum of a two fingers in this space. So in the absence of a radiograph a clinician should be able to evaluate through palpation the loss of functional sub-cranial space.

Functionally there needs to be a space between the occiput and Atlas, and their needs to be a space between Atlas and Axis. These spaces are supposed to be proportional, 6.5mm +/- 2.5mm and the spaces can vary between 4 and 9mm (Rocabado, CF2, CF3 2013).

The spaces between occiput and Atlas and the spaces between Atlas and Axis can decrease. If C2 shifts, it can go into a state of immobilization and the spaces can cause a mechanical entrapment of the neuro-vascular structures which can cause headaches and facial pain (Rocabado, CF2, CF3, 2013).

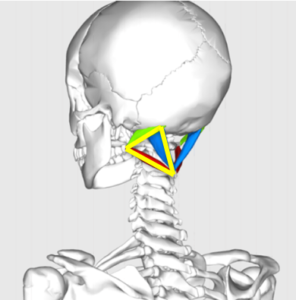

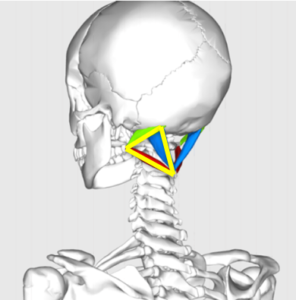

The landmarks of the suboccipital triangle include the basi occiput superiorly, spinous process of C2 inferiorly and transverse process of C1 laterally. Three muscles of the border the triangle include: Rectus Capitis Posterior Major (above and medially), Obliquus capitis superior (above and laterally) and Obliquus capitis inferior (below and laterally). The floor is formed by the posterior occipito-atlantal membrane, and the posterior arch of the atlas. Palpation in the suboccipital triangle can help us determine the functional sub-cranial spaces and serving as a provocation test for the soft tissue in this area.

The suboccipital Triangle (yellow triangle) – provocation test.

The effect of occlusal changes on the sub-cranial angle

Lowering of the mandible leads to a temporary increase in cranial backward bending. The posture of the head has been found to change immediately following an “opening of the bite” – with an increase in vertical dimension anteriorly (a.k.a. lowering of the mandible). Using an inter-occlusal appliance, normal individuals were subjected to an opening of the bite, ranging from 0.3-9º. Within one hour a posterior rotation of the head was found in 90% of the subjects. Physical therapists must be aware that wearing an appliance will have this effect and this may lead to symptoms in some of our patients. Patients with an ample sub-cranial functional space are going to tolerate this change in the sub-cranial angle, but for someone who already has a narrow craniovertebral angle (<96º) this might lead to symptoms.

A physiological cervical lordosis is seen with a craniovertebral angle between 96ᵒ-106ᵒ. Non-physiological cervical postures are seen with craniovertebral angles <96ᵒ (posterior cranial rotation, lower cervical spine moves into flexion/inverted cervical lordosis) and >106ᵒ result in anterior cranial rotation.

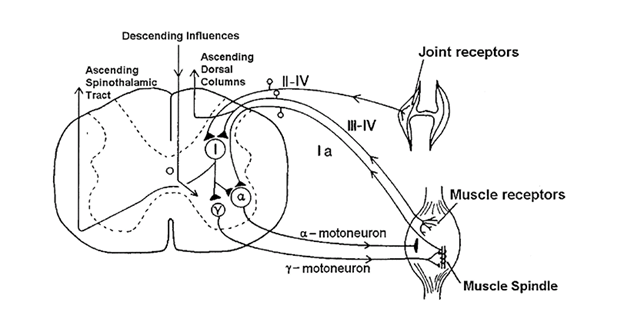

Trigeminal cervical nucleus

The trigeminal cervical nucleus is located in the center of the upper cervical spinal cord and it has three branches: V1, V2, and V3. The first cervical vertebral (C1) corresponds with V1 branch of trigeminal cervical nucleus which innervates supraorbital area of the face. The second cervical vertebral (C2) corresponds with V2 branch of the trigeminal cervical nucleus which innervates infraorbital area of the face. The third cervical vertebral (C3) corresponds with V3 branch of the trigeminal cervical nucleus which innervates the mandibular area of the face. Understanding the anatomical relationship between the upper cervical spine and the trigeminal cervical nucleus will help the physical therapist identify segmental dysfunction based on pain patterns of the face and head. Also, it is important to know that the position of C2 will influence the functional spaces of the cervical spine posteriorly which can contribute to headaches and facial pain of a cervical origin.

The cervicogenic headaches are pain that refers to the head from a source in the cervical spine. Unlike other types of headaches, cervicogenic headaches has attracted interest from disciplines outside of neurology. Orthopaedic manual physical therapist, dentist in the area of craniofacial and oral pain, and interventional pain specialist (anesthesiologist) have developed an interest this headache treatment (The Lancet, 2009). Cervicogenic headache are the best understood of the common headaches. The mechanism is known, and these headaches have been induced experimentally in healthy volunteers. In some patients, cervicogenic headaches can be treated temporarily by diagnostic blocks to the cervical joints and nerves (International Headache Society, 2004).

The convergence of cervical and trigeminal afferents on second-order neurons in the trigeminocervical nucleus may refer pain from the upper cervical spine into the head and face. Furthermore, “bi-directional interactions” between trigeminal and upper cervical afferents may also explain neck symptoms of trigeminal origin (EG, Migraine) (Dreyfus, 1994).

Every time there is a loss of space in the craniovertebral angle you lose the distance between the spinous process of C2 and occiput. When the distance or space between occiput and C2 is lost it will cause the Atlas to try to find a way to maintain a functional space and the Atlas will no longer have any functional space. Physical therapy treatment should focus on increasing or opening up the space between occiput and C2 to allow the atlas to have space between occiput and C2.

If there is a loss space between occiput and atlas or Atlas and Axis, or both, the patient could also have a loss of space in the craniovertebral angle. If the position of C2 changes, the spaces will change and the cranial nerves and vascular structures can become entrapped. C2 becomes the most important vertebrae to treat in this condition of trying to find a horizontal position for the cranial and for a stable craniovertebral system.

X-Rays will show if the space between occiput and C2 or occiput and atlas have decreased. If those spaces have decreased, they form an entrapment for the ligaments and others tissues in that area and that can lead to headaches. A physical therapist must manually open up those spaces. The space between occiput and C2 should be at least 20 mm.

To manually assess this space you should palpate the spinous process of C2 and then side bend the head to the left and right to feel C2 rotate. The physical therapist should be able to feel the space between occiput and C2 and the movement of C2. Fifty percent (50%) of the rotation of the head takes place at Atlas and Axis with the occiput on top. The occiput and Atlas uses the dens as an Axis of rotation and it allows the head to rotate right or left. If the patient turns their head to the right the patients head should go from the sternum to the most prominent portion of the shoulder laterally.

The patient should have 50% rotation to the right, and 50% rotation to the left. The flexion-rotation test is one of the best ways to prove craniofacial pain or headaches of cervical origin.

Atlas can be related to the wings on a plane. When the plane needs to turn right, the right wing drops down and goes back while the left wing goes up and forward. When the plane needs to turn left, the left wing goes down and back while the right wing goes up and forward. If the transfer process of Atlas is more prominent on the left side, it means that it rotated to the right. If the transfer process of Atlas is more prominent of the right side, it means that it rotated to the left.

Manual Therapy Treatment to Increase Subocciptal Spaces

So the physical therapist will need to change the position of C2, and by doing so you will open up or increase the space between occiput and C2 and this will help atlas to restore functional space with occiput and axis.

When treating TMD it is important to note that:

- Some problems can be caused by the neck, in which case it is important to stabilize the cervical spine.

- When dentists look at teeth, they should find at least one contact that is wrong.

- The physical therapist should continue to stabilize cervical spine.

- Have an objective concept with your patient’s dentist. Relay evaluation measurements and findings.

- Accomplish a state of rest for TMJ and cervical joints.

- Occlusion contacts will continue to change with treatment. It will be important for the patient to follow up her/his dentist throughout treatment.

- Breathing patterns may be evaluated in patients who have sleep apnea.

- You want the muscles to relax in order to find a stable position.

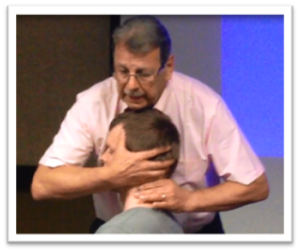

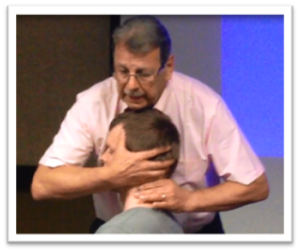

Manual Therapy Treatment Technique (in sitting) to Increase Subocciptal Spaces

- Place patient is a seated position with the malar bone over the sternum.

- Palpate the subocciptal triangle. Assess for provocation of pain or symptoms.

- Alar ligament test – Side bend (or laterally rotate the cranium) C2 should rotate in the same direction. Assesses the stability of the Alar ligament on the opposite side of the side bending.

- Determine the position of C2-C3 by evaluating sidebending and look for right and left motion restriction and asymmetry.

- Evaluate Atlas rotation by fully flexing (anteriorly rotating) the cervical spine and assess the cervical spine rotation left and right.

- Long axis traction/distraction of C2-C0 in sitting.

- 6 times with 6 second holds

- The purpose of the distraction force is to lubricate the joints

- With inspiration the head moves up as the curvature of the spine straightens and with exhalation the head moves down as the spine returns to a resting curvature. This movement produces the force for distraction.

- When the patient breaths in, the head moves up and the physical therapist supports the head with one hand and the exhalation produces a nature distraction. The muscles also relax with exhalation and the weight of the body produces a distraction force with the body moving away from the head.

- The fingers of the mobilizing hand should be placed over the mastoid process, hand / thumb over the malar bone and the thumb in front of the ear.

- To produce a specific distraction the physical therapist uses the opposite hand to stabilize C2 laterally over the transverse processes. The stabilizing hand should be not aggressively hold down C2.

Figure 1: Long Axis Traction/Distraction

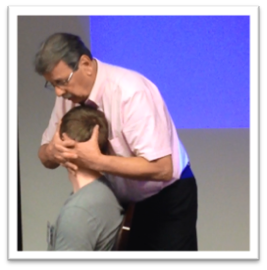

- Long axis traction/distraction of C2-C0 with cranium side bending (lateral rotation of the cranium) in the direction of the restriction. Once side bending (lateral rotation) movement improves rotation to the opposite direction can be added.

- Follow the same steps noted above and then add gently side-bend/mobilize head towards the motion restriction while the distraction force in maintained.

- The goal is to lubricate the cervical joints and to improve side bending (lateral rotation) mobility in the direction of the restriction.

- The physical therapist stands on the opposite side of the side bending.

- The amount of side bending (lateral rotation) and rotation is approximately 11 mm (less than .5 inch) in each direction.

- Eventually side bending and rotation movements can be combined.

- When performing right side bending (of the cranium) mobilization with left rotation the C2 is being mobilized on C3 and the right C0 on mobilized on C1.

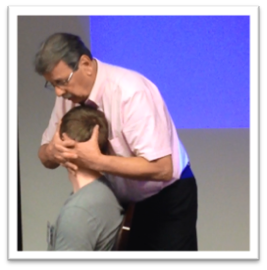

Figure 2: Long Axis Distraction with Right Lateral Rotation

Figure 3: Long Axis Distraction with Right Lateral Rotation with Opposite Rotation

- Occiput “Lift”

- Cross hands around the malar bone in order to have good control of the head and face. Take the neck to end range rotation in the direction of the restriction.

- While in end range rotation, have the patient inhale and then exhale to produce a quick distraction force/”occiput lift”. The mobilization occurs at the end of the exhalative breath.

Figure 4: Occiput “Lift”

The objective of this sequence of techniques is to initially identify upper cervical spine mobility restrictions. Then treat the hypomobile joints by first lubricating the joints through gentle long axis distraction and then progress the treatment to mobilizing the joint in the direction of the hypomobilty/restriction. Rocabado progresses the treatment from long axis distraction, to long axis distraction with side bending (lateral rotation), and then long axis distraction with side bending (lateral cranium rotation) with horizontal rotation. Finally, Rocabado does a distraction mobilize (approximately a grade IV-V) of the CO/C1 joint while at end range horizontal rotation.

Rocabado describes the Atlas (C1) as being “like a disc” functioning between C0 and C2. This treatment sequence mobilizes the inferior joint surface of C1 by mobilizing C2 (rotation of C2 on C1) and mobilizing the condyles of the occiput on Atlas. The Atlas receives a maximum amount of mobilization without moving the Atlas itself.

Conclusion

This project was intended to provide an overview of knowledge attained while studying with Mariono Rocabado and not his complete and comprehensive craniovertebral evaluation / treatment approach. The foundation of Rocabado’s evaluation approach lays in assessing the upper cervical stability, in particular the sagittal and coronal planes, and this was outlined in this capstone project. In addition, Rocabado stresses the importance of preparing joints for treatment in a gradual progressive manner. A sample treatment was outlined so the reader could appreciate Rocabado’s principle of a progressive treatment approach.

References:

- Dreyfus P; Michaelson M, Fletcher D, Atlanto Coppipital and Lateral Atllanto Axial Joint Pain Patterns. Spine 1994; 1: 1125-31.

- International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd. Edition Cephalalgia 2004; 24 (SUPPL. 1) 115-116.

- Mariano Rocabado. January 2013. Basic Cranio-Facial (CF1). University of St. Augustine. Online course.

- Mariano Rocabado. February 2013. Intermediate Cranio-Facial (CF2). University of St. Augustine. Chicago, IL.

- Mariano Rocabado. February 2013. CF3 – Advanced Cranio-Facial (CF3) University of St. Augustine. Chicago, IL.

- thelancet.com/neurology Vol. 8, October 2009

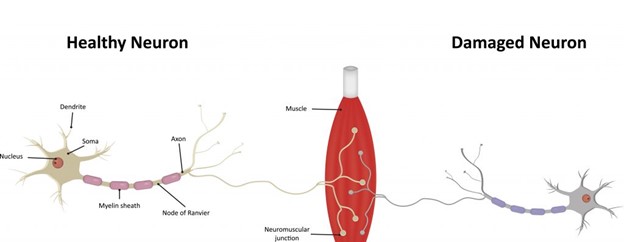

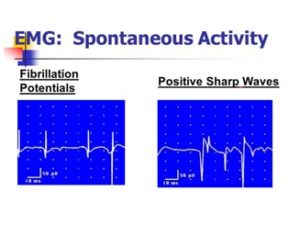

Of note, there was minimal palpable contraction of the right gastroc-soleus during resisted plantarflexion. No significant lumbar or other orthopaedic abnormalities were found during the examination. Robert was instructed in some lower extremity therapeutic exercises and we attempted to finish the session with Russian muscle stimulation to the right gastroc. Interestingly, Russian stimulation was unable to evoke muscle activation or twitch response from Robert’s gastroc-soleus, though he did feel increasing tingling sensation, a finding I had not previously seen in eight years of experience.

Of note, there was minimal palpable contraction of the right gastroc-soleus during resisted plantarflexion. No significant lumbar or other orthopaedic abnormalities were found during the examination. Robert was instructed in some lower extremity therapeutic exercises and we attempted to finish the session with Russian muscle stimulation to the right gastroc. Interestingly, Russian stimulation was unable to evoke muscle activation or twitch response from Robert’s gastroc-soleus, though he did feel increasing tingling sensation, a finding I had not previously seen in eight years of experience.  Segmental facilitation can cause muscle tenderness, hypo or hyperreflexia, altered skin and muscle sensitivity, muscle hypertonicity, inhibition of antagonist muscle groups, and muscle weakness that it typically not fatigable. Pettman discusses common segmental facilitation at C2/3, C5/6 and L4/5, though it can occur at any spinal segment. “It is proposed that the constant afferent barrage ultimately leads to a state of ‘central segmental excitation’ that, in turn, lowers the synaptic resistance and facilitates neuronal transmission” (Pettman 2005). Furthermore, as discussed throughout the lab courses in the Fellowship program, manual therapy treatment to the axial spine can be beneficial in improving peripheral signs and symptoms.

Segmental facilitation can cause muscle tenderness, hypo or hyperreflexia, altered skin and muscle sensitivity, muscle hypertonicity, inhibition of antagonist muscle groups, and muscle weakness that it typically not fatigable. Pettman discusses common segmental facilitation at C2/3, C5/6 and L4/5, though it can occur at any spinal segment. “It is proposed that the constant afferent barrage ultimately leads to a state of ‘central segmental excitation’ that, in turn, lowers the synaptic resistance and facilitates neuronal transmission” (Pettman 2005). Furthermore, as discussed throughout the lab courses in the Fellowship program, manual therapy treatment to the axial spine can be beneficial in improving peripheral signs and symptoms.