Meniscus? What’s that?

Introduction

Meniscus. It’s a strange word, right? Many people are not aware that the meniscus is the protective covering over the lower leg (tibia) which forms cushion and support for the knee (20 from CPG). There are many functions of the meniscus, including to facilitate joint gliding or movement, prevent the knee from over-extending, provide nutrition to the knee, serve as a support for the knee, and provide shock absorption (1). The meniscus is rarely strained like other structures of the body, but it can become injured through “wear and tear” over time or a specific acute injury in which a person feels a catch or a pop in the knee. The type of injury that occurs determines whether the person is more likely to benefit from physical therapy or surgery for treatment. Surgery is very common for this injury. In the United States, meniscal surgeries account for 10%-20% of all orthopedic surgeries which represents about 850,000 meniscus surgeries every year (2).

Should I have an MRI or X-Ray?

If you have had any type of injury to your knee, whether it is meniscal-related or not, the following guidelines are used to determine whether imaging such as an MRI or X-ray is appropriate. These guidelines, called the Ottawa Knee rules, recommend having an MRI if you meet any of the following criteria after a traumatic knee injury (3,4):

- Age 55 or older

- Isolated tenderness to your kneecap

- Tenderness to the touch at the head of your fibula (just below your lateral or outside knee)

- Inability to flex the knee to 90 degrees

- Inability to bear weight immediately or unable to take 4 steps

Should I have surgery?

This is a very common question and the answer is complex. Evidence from a study in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrated that among people with a meniscal tear and knee osteoarthritis at 6 months and 12 months, there were no clinical or significant differences found in functional outcomes between those who had surgery and those who did not (5). What does this mean? Surgery for a torn meniscus, especially one that is naturally worn over time as compared to a specific traumatic tear, often results in no benefit compared to performing non-surgical physical therapy. Physical therapists are clinical experts in diagnosing and treating meniscus injuries. Let’s take a look at what the latest research says about how physical therapists can help patients with meniscus injuries.

2018 Clinical Practice Guidelines for Meniscal Lesions

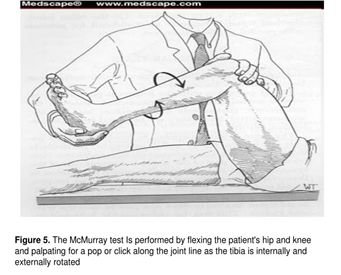

First, your physical therapist will want to find out about the history of your mechanism of injury: What happened? Did you twist your knee? Did you feel a sharp pain? Is your injury tender to the touch? Are you able to put weight through it? How swollen is your knee? How bad does it hurt? Does it feel like it catches, locks, or buckles? What makes it feel better and what makes it feel worse? Does it have sharp infrequent pain or is it a subtle pain that is there almost always when you put weight through it? All of these questions will help to guide the physical therapist in performing objective tests to determine the diagnosis and severity of the injury. This examination will also include assessing the flexibility and strength of the hip, knee, and ankle and functional challenges such as climbing the stairs, walking for 2 to 6 minutes, and hopping on one leg. After these assessments are performed, the final step is performing specialized tests that are specific to the meniscus, including the “McMurray Manuever”. The McMurray Maneuver is the best test for assessing a meniscal injury according to the 2018 Meniscus Clinical Practice Guidelines and is defined as follows (6,7,8,9):

“With the patient supine the examiner holds the knee and palpates the joint line with one hand, thumb on one side and fingers on the other, whilst the other hand holds the sole of the foot and acts to support the limb and provide the required movement through range. From a position of maximal flexion, extend the knee with internal rotation (IR) of the tibia and a VARUS stress, then return to maximal flexion and extend the knee with external rotation (ER) of the tibia and a VALGUS stress.[1][2][3] The IR of the tibia followed by extension, the examiner can test the entire posterior horn to the middle segment of the meniscus. The anterior portion of the meniscus is not easily tested because the pressure to that part of the meniscus is not as great. Positive findings for the McMurray Maneuver include pain, snapping, audible clicking or locking can indicate a compromised meniscus.”

Image above courtesy of www.medscape.com

Intervention/Treatment

The following exercises are recommended for persons with a meniscal injury who did not have surgery:

- Progressive range of motion and flexibility of the knee all directions

- Progressive strength training of the knee and hip musculature

- Neuromuscular re-training such as balance activities

What is the goal of rehab for a meniscal injury? As with most joint injuries, the primary goal is to return to your normal function as soon as possible. In order to do this, you will work with your physical therapist to improve knee flexibility, progress the strength of all the muscles of your hips and knees which also provide support to your meniscus, and improve your balance and control. This will allow you to return to your daily activities pain free and prevent other meniscus injuries in the future.

Physical Therapy First

The orthopedic specialist at Physical Therapy First will provide you with the highest quality care based on the latest research combined with decades of clinical experience to assist in decreasing the swelling of your knee, returning your knee to full range of motion, and helping you to create an individualized exercise program that will allow you to avoid surgery and experience a higher quality of life. Our therapists provide 1-on-1 treatment sessions with all patients for one hour and offer the best care you will receive in the greater Baltimore area. Call any of our four clinics to schedule an assessment today.

References:

- Brindle T, Nyland J, Johnson DL. The meniscus: review of basic principles with application to surgery and rehabilitation. J Athl Train. 2001;36:160-169.

- Renström P, Johnson RJ. Anatomy and biomechanics of the menisci. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9:523-538.

- Bachmann LM, Haberzeth S, Steurer J, ter Riet G. The accuracy of the Ottawa knee rule to rule out knee fractures: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:121-124. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00013

- Stiell IG, Greenberg GH, Wells GA, et al. Derivation of a decision rule for the use of radiography in acute knee injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:405-413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70106-0

- Katz JN, Brophy RH, Chaisson CE, de Chaves L, Cole BJ, Dahm DL, Donnell-Fink LA, Guermazi A, Haas AK, Jones MH, Levy BA, Mandl LA, Martin SD, Marx RG, Miniaci A, Matava MJ, Palmisano J, Reinke EK, Richardson BE, Rome BN, Safran-Norton CE, Skoniecki DJ, Solomon DH, Smith MV, Spindler KP, Stuart MJ, Wright J, Wright RW, Losina E. Surgery versus physical therapy for a meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2013 May 2;368(18):1675-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301408. Epub 2013 Mar 18. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2013 Aug 15;369(7):683. PMID: 23506518; PMCID: PMC3690119.

- Magee, D.J Chapter 12: Knee, in Orthopedic Physical Assessment. Pg 791. Saunders Elsevier. 2008.

- Piantanida, A.N. Yedlinsky, N.T. Physical examination of the knee, in The Sports Medicine Resource Manual, Editors: Seidenberg, P.H & Beutler, A..I. 2008 Saunders. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-3197-0.X1000-2.

- Waldman,S.D. Painful conditions of the knee, in Pain Management Vol 1., 2007. Saunders. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-1-59662-1.

- Logerstedt DS, Scalzitti DA, Bennell KL, Hinman RS, Silvers-Granelli H, Ebert J, Hambly K, Cary JL, Snyder-Mackler L, Axe MJ, McDonough CM. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2018;48(2):A1-A50. Knee Pain and Mobility Impairments: Meniscal and Articular Cartilage Lesions. doi:10.2519/jospt.2018.0301